The Process of Mastering a Skill

In the first part of this mini-series “The Paradox of Choice”, I talked about the psychology behind making choices when overloaded with information. Here I will cover the process of mastering a skill and how to put it into practice in a world full of distractions.

This post is inspired by Mastery by Robert Greene and Deep Work by Cal Newport. I highly recommend reading both, as they will help you understand the process of mastering a skill or field.

Prodigy or Expert?

Have you ever wondered what separates experts from everyone else? I don’t mean the self-proclaimed “experts” who value status over learning. I mean the “geniuses” of our industry who know their field extraordinarily well and have spent decades honing their skills. How do these successful researchers master their field? Is it some natural talent they were born with, or do they have a magic trick that only a few know about?

When performance psychologists studied what distinguishes experts across several different fields, they kept coming across the same answer in each field: deliberate practice.

In his 1993 paper The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance, K. Anders Ericsson stated:

We deny that these differences are immutable, that is, due to innate talent. Only a few exceptions, most notably height, are genetically prescribed. Instead, we argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain.

K. Anders Ericsson

Today we know that it’s not magic. It’s this specific form of practice. If you look at the so-called “geniuses” throughout history, time and again the common factor is not innate talent, but just that they each put countless hours into mastering their craft long before arriving at their respective breakthroughs.

Does that mean you can become the next Einstein? Yes. But not if you waste your time with unstructured learning. If you structure your approach to learning, apply solid discipline and rebuild your own brain’s ability to focus, you can achieve truly great things. The trick is to focus on deliberate practice rather than on practice alone. You will read about the difference between the two in section Deep Work, or in my previous blog post on The Importance of Deep Work.

In his book The Laws of Human Nature, Greene notes that mastering a skill that matches your interests gives your brain the sense of purpose and direction that it craves. This is important when learning something new, because practice can otherwise be tedious and cognitively demanding. Clear goals let us embrace this process, knowing that the eventual reward will outweigh the sacrifice. This, in turn, makes the process more pleasant. Eventually your mind develops enough discipline to withstand distractions and becomes pleasantly absorbed in the work. This is how we achieve focus and momentum. In this state of flow your brain retains more information and so you learn even faster.

It is easy to get overexcited and want to learn many skills all at once. I could do this, I could do that. No, you can’t. You can’t do everything at once, and you are not meant to do everything in life. Focusing on one activity should not frighten you; it should liberate you. Developing solid skills in one area lets you branch out to something else and to combine different skills. If you are someone who gets easily bored, you can follow the path of doing different things, but doing so by mastering each before advancing to the next.

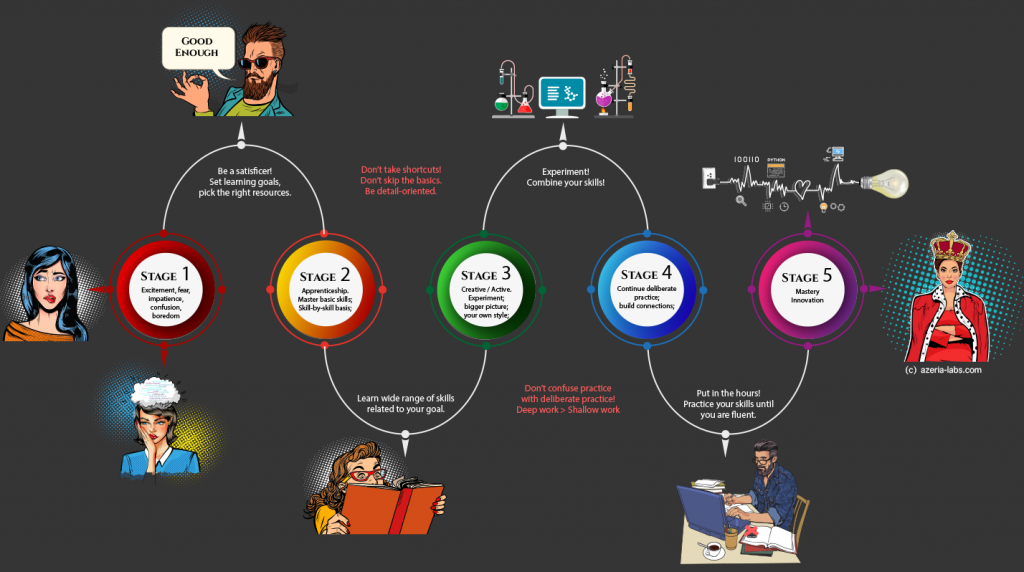

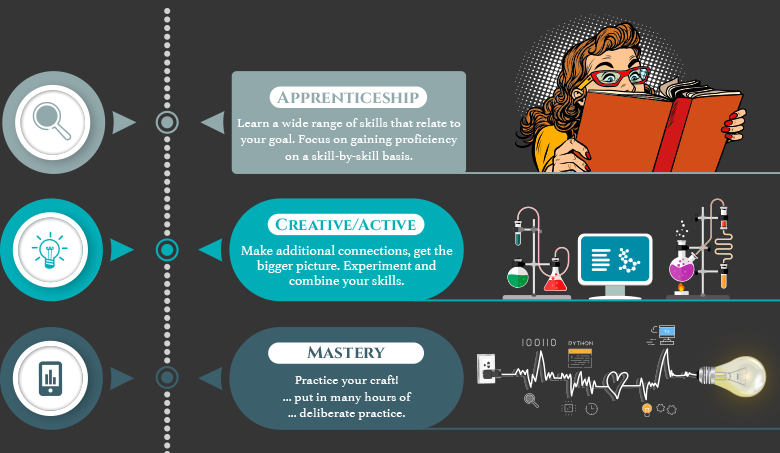

Mastering a skill or field is a challenging but fulfilling and rewarding feeling. It takes patience, dedication, and discipline. If you feel like you lack these things, don’t be discouraged. Part of the process is to develop skills like discipline and patience on your way to mastery. Once you have mastered one skill or field, it will be much easier to move on to the next one because you will have developed the brain muscles and the skills that make it easier for you to structure your learning and retain information in a more efficient way. Greene breaks this process down into three stages: “apprenticeship”, the “creative/active” phase, and finally “mastery”.

Stage 1: Apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is the stage where you learn a wide-range of skills related to your chosen field. In this stage you should identify which skills are the most important to learn and prioritize these, gaining proficiency on a skill-by-skill basis. It is better to learn one skill at a time, rather than trying to multitask and learn them all at once.

During this stage it is okay to mirror the techniques of others and try them yourself by, for example, following online tutorials or reinventing well-known tools for yourself. But it is also important to get out of your comfort zone and not shy away from difficult problems or obstacles.

Apprenticeship can be the most challenging of the three stages of mastery, but it is also the most important. So here are some things to keep in mind as you are going through this stage:

- Value learning over money: During this stage, focus on mastery, not money. Be patient and remember that the eventual reward will outweigh the sacrifice.

- Don’t focus on status. Don’t focus on proving yourself to others and showing off what you know. Instead, focus on teaching other what you have learned. Sharing your knowledge with others by, for example, writing blog posts is a great way of filling your gaps in understanding a subject. If your writing focuses on trying to explain a concept well to the biggest possible audience, you will help develop your own understanding of the skill as well as learn how to explain complex topics to a broader audience. But be careful: if you set out to show-off and sound “smart” in your blog posts you will end up leaving out important context from your posts, fail to admit how you overcame obstacles, and end up putting others off and looking like a jerk.

- Don’t pay much attention to what others think. If you focus too much on what others think of you, it will make you feel insecure and distract you from learning. Remember: in this stage you are still learning and that’s okay; it doesn’t matter that you’re not an expert yet. If you instead set clear goals and have a sense that you are advancing, you will focus more on the quality of your work. This will also help you distinguish between constructive versus malicious criticism.

- Keep expanding your horizons: Exchange ideas with people from your industry and hang out in a hacker space or conference every now and then. These experiences and connections all contribute to your learning. Talk to people about your current projects and ask them about theirs rather than trying to show off.

- Embrace the feeling of inferiority: If you feel like you already know something or have mastered it, you stop learning. Always assume that you are a beginner and that there’s more to learn. There’s always more to learn. A sense of superiority can make you fragile to criticism and too insecure seek help or improve.

- Trust the process: It takes time. Nobody masters a skill overnight. But this should motivate you rather than discourage you. After all, if mastering a skill was easy, the skill would have little value. Try to align your individual interests in a field to identify a niche that you can dominate.

- Move toward resistance and pain, avoid the easy path: It is very human to avoid our own weaknesses, and so stretching our mind to its limits can feel uncomfortable. This leads most people to stay in familiar territory rather than advancing to new things. If you want to achieve mastery, you must instead follow the “resistance path”. Pick challenges that are slightly above your skill level to help you advance. Avoid challenges that are either way too far beyond your skill which might discourage you, or those below your skill level which will bore you and cause you to lose focus.

- Get used to failure and embrace it as a critical part of learning: When a computer program malfunctions, it shows you that you need to improve it. Treat your own failures the same way: as opportunities for improvement. Failures make us tougher and show us how something doesn’t work. Failures are learning opportunities giving you a new experience to learn from.

- Master the art “what” and the science “how” of everything you do: Get a full understanding of the skill, not just the tools, or one narrow technique. It is totally okay to get familiar with all the tools Kali Linux has to offer, but your aim should be to understand the inner workings behind the techniques that are being used by these tools. Don’t be afraid to “reinvent the wheel” by building your own versions of existing tools–this can also help you to internalize a concept.

- Advance through trial and error: Be curious! Try out new things! If you wonder if something would work in practice, try it out and see. If it works, great. If not, you’ll have learned why it doesn’t work.

Stage 2: Creative-Active

The creative/active stage occurs after you’ve established a solid foundation in the skills of your chosen field. In this stage you combine these skills together in new and more interesting ways. Unlike the apprentice stage, where you tried and learned pre-existing techniques, here you combine them to come up with your own and develop your own unique style to execute your craft like nobody else.

Some people try to jump straight into this stage and skip the apprenticeship stage. These people usually fail because inventing something new without knowing what’s already out there or having a firm understanding of the basis of the skill is very frustrating and difficult.

Often this aspect of mastery can seem scary. You are venturing into places no tutorials exist and trying to use your skills in ways nobody else has before.

Stage 3: Mastery

The final stage is where all the hours of work finally pay off… Mastery!

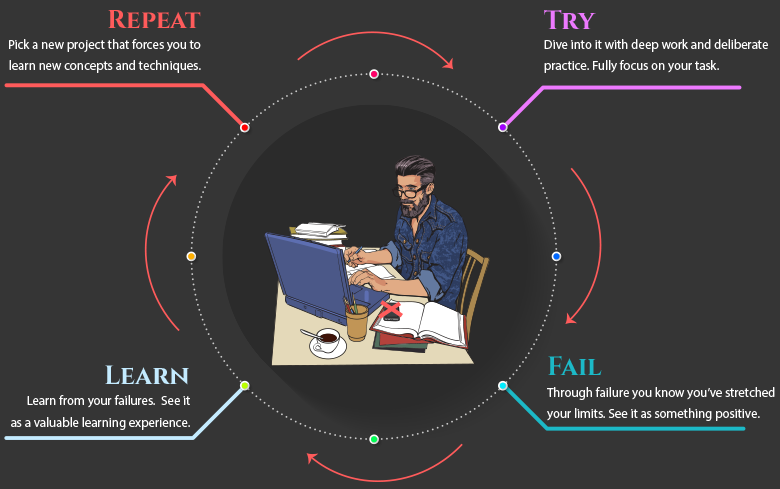

The entire process can be summarized as follows. Click to enlarge the image.

To finally achieve mastery, you’ll need to learn how to manage distractions, how to reach flow, and how to embrace deep work, and recognize that it is deliberate practice, not just hours spent in front of a computer or a book that determines how fast you will achieve mastery.

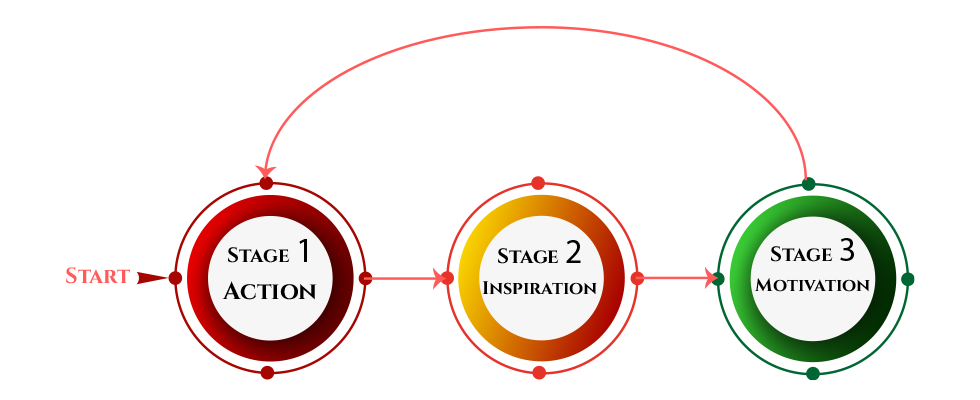

Motivation

Each of us knows what it is like to be distracted and be unproductive. We often wait for motivation to strike and inspire us to start our project. But we don’t have to wait for motivation to appear out of nowhere; we can instead induce motivation. In my experience, motivation happens when we start with action, which in turn sparks inspiration, and this inspiration gives us motivation to go further in a self-reinforcing loop.

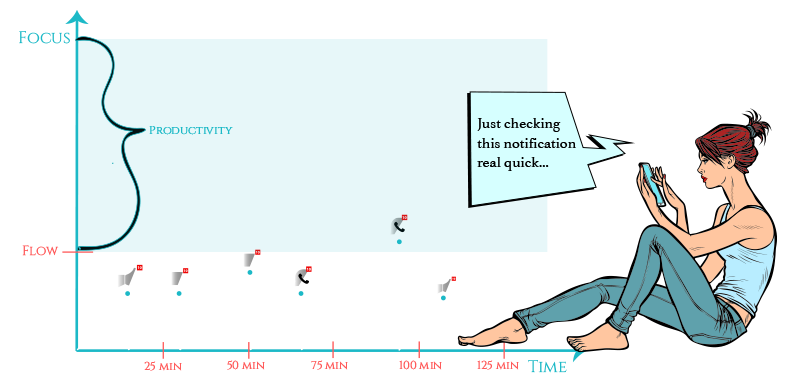

Even once we are motivated to action, it is easy to tinker around without direction or become distracted by social media and phone notifications. If we allow ourselves to get distracted, eventually we will see that time passes quickly, but we don’t get much done. Managing and minimizing distractions is therefore critical to achieving flow and making best use of time.

Flow

I covered the concept of flow and Deep Work in my blog post The Importance of Deep Work in more detail. Flow is the momentum you reach when you are fully focused on a task and everything seems to flow effortlessly. Flow can be quite addictive. Those who have experienced flow know that it feels like you’re in a meditative state of productivity. It feels calming and gives you a sense of purpose. This rewarding feeling of flow is best described by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi:

The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

The 25-minute Rule

In a study from the University of California Irvine, researchers studied the costs of interrupted work. According to the study, it takes an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to get back to the task after being interrupted. Interrupted work also caused participants of this study to experience higher levels of stress, frustration, and mental exhaustion.

A good rule of thumb is that it takes about 25 minutes of undistracted focus to reach a state of flow. This means if you’re checking your phone notifications every 20 minutes you will never reach this state. Apps are designed to keep us in front of our screen as much as possible. It’s a battle for attention; a cascading waterfall of notifications. We unlock our phones 80 times per day on average.

New versions of Android and iOS have a new “Screen Time” feature. This shows you statistics of how much time you spend staring at your screen, what apps you use the most, and now many times you unlock your phone. Check it out: you might be surprised how much time and focus apps are draining from you each day.

Even if we know how much time we waste on our phone, it can still be difficult to battle it and focus on what is important. To help, I will cover some of the apps that help me stay focused at the end of this blog post.

Deep Work

In Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, Newport writes:

Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive ability to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skills, and are hard to replicate. Deep work is hard and shallow work is easier and in the absence of clear goals for your job, the visible busyness that surrounds shallow work becomes self-preserving.

Cal Newport

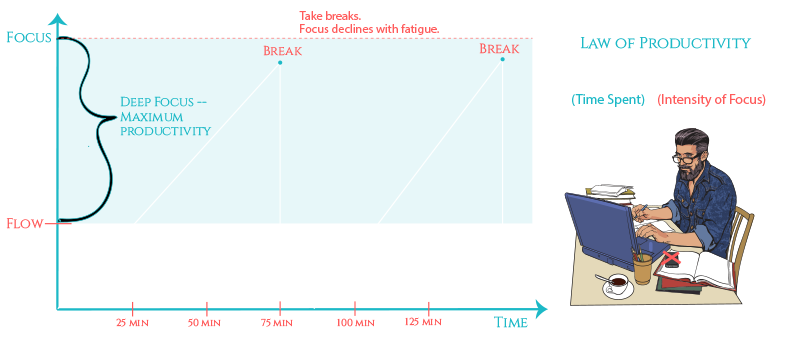

In his research Newport discovered that high-performing students exemplified the following rule:

Work Accomplished = Time Spent x Intensity

This rule is why some students spend all night studying and still struggle, whereas others easily outperform them. I wish I had understood this rule when I was an undergraduate during exams. Only later I realized that time spent “studying” doesn’t make much difference if the time spent is not high-intensity. Once I understood this, I could avoid all-nighters and accomplish far more in much less time. The secret is to systematically increase the intensity levels of your focus by experimenting with various techniques that fit your specific lifestyle and brain.

My approach is to split my projects into deep work sessions. I make a list of things I want to accomplish and focus on the task for 90-120 minute periods, followed by a short break, and then repeat. You’d be amazed how much you can get done in a 4 hour block of uninterrupted work.

Deliberate practice is purposeful, systematic, and stretches your mind to its limits. It requires focused attention and is performed with the goal of improving performance. Regular practice is basically mindless repetition of the same task. The more we repeat a task, the more mindless it becomes. Mindless activity is the enemy of deliberate practice.

You need get used to failure and embrace it as a critical part of learning.

Productivity Apps

Devices are usually the source of our distractions, but there are a few apps we can use to help increase productivity. Here are some of my favorite apps that I use to reduce distractions when working:

Screen Time:

If you have an iPhone, use this feature! It tells you the unvarnished truth about your app use. You can set limits on specific apps or categories of apps, like social media. Once you reach the limit, the apps will be disabled. You can re-enable access for another 15 minutes each time you reach your limit. Personally, I limit social media access to 30 minutes per day when I’m not traveling.

Trello:

I use Trello boards to manage and plan my projects. Trello helps you create project boards, to-do lists, set deadlines, and so on. One of my boards serves as my weekly to-do list and is called “Weekly”. For individual projects I use boards listing different project stages and a to-do list for each.

Your project to-do list doesn’t need to detail your entire plan right from the start. Your first project to-do list should instead contain small steps to get your project started. Make it as small as possible, listing 10 items or so. This will help you get started and help you progress step-by-step without getting stuck on what to do next. As you work through your to-do list you will come up with more items and can add them to the list as you go.

Try to create to-do list items that represent clear instructions of what to do next, so whenever you look at the list you know exactly how to proceed. For example, suppose that you need to prepare a presentation. A to-do list containing items like “create outline”, “create all graphics”, “create slides” and “finish slides” is too abstract, and you might spend too much time splitting the task up in your head and forgetting what to do next. A better approach would be to split each step into small tasks, such as the following:

- Create outline

- Map out the different sections

- Map out the different subsections

- Create graphic for slide X

- Create graphic for slide Y

Forest:

This is my favorite app, as it is both simple and useful. Whenever I decide to focus on a task for an hour or two, I set my Forest timer and hit “plant” to plant a tree of my choosing. If you switch to another app while the tree is growing, the tree will die. If you manage to avoid switching apps until your period of focus is done, you get a tree and points that can be spent on new types of trees and bushes for your Forest garden.

The app is very simple and has the psychological effect of rewarding you for remaining undistracted. It helps make focus a habit and teaches your brain that it’s time to ignore distractions and to focus as soon as you press the “plant” button.

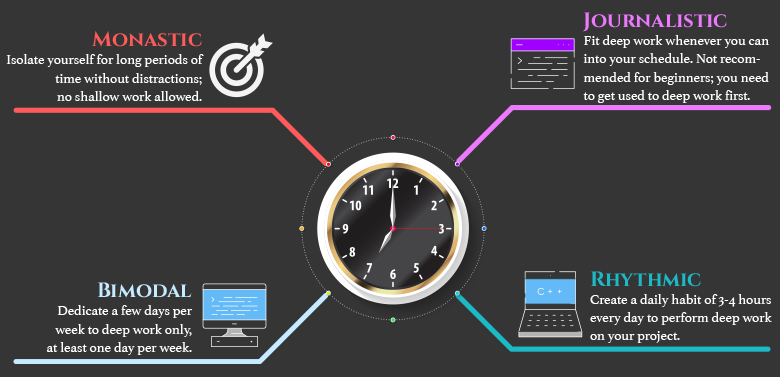

Make Deep Work a Habit

Don’t just do deep work every now and then. Make it a habit! You need to choose a strategy/philosophy that fits your specific circumstances, as a mismatch can derail your deep work habit before it has a chance to solidify. Here are some strategies I extracted from the book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World:

- Monastic: “This philosophy attempts to maximize deep efforts by eliminating or radically minimizing shallow obligations.” — isolate yourself for long periods of time without distractions; no shallow work allowed.

- Bimodal: “This philosophy asks that you divide your time, dedicating some clearly defined stretches to deep pursuits and leaving the rest open to everything else.” – dedicate a few consecutive days (like weekends, or a Sunday, for example) for deep work only, at least one day a week.

- Rhythmic: “This philosophy argues that the easiest way to consistently start deep work sessions is to transform them into a simple regular habit.” – create a daily habit of three to four hours every day to perform deep work on your project.

- Journalistic: “in which you fit deep work wherever you can into your schedule.” — Not recommended to try out first, since you first need to accustom yourself to deep work.

Book Recommendations

If you are serious about mastering a skill in your field, I recommend getting some context and reading books that provide you with practical knowledge and put you into the right mindset. Here are some books I highly recommend, ordered by usefulness and importance.

- Mastery – Robert Greene

- Deep Work – Cal Newport

- The Subtile Art of Not Giving a Fuck – Mark Manson

- The Power of Habit – Charles Dugigg

- Atomic Habits – James Clear

- The Paradox of Choice – Barry Schwartz