Recently I gave a keynote at the RoadSec conference in São Paulo about learning and mastering new skills and a problem called “choice overload” that affects nearly everyone starting out in our industry. You can download the slides of my talk here.

In this mini-series I want to cover this topic in a little more detail based on various conversations I’ve had with several newcomers and experienced security veterans in InfoSec. During these conversations I realized that I was not alone in often having mixed feelings of excitement and confusion when learning new topics and I decided to read and study the psychological phenomena behind it.

This first part of my mini-series covers the question I get asked the most, namely “I want to learn X, where do I start?”. Whenever someone asked me about resources for a given topic, I sent them a collection of resources they can choose from. Interestingly, this pool of resources didn’t really help them pick the right ones to finally start learning. This made me curious.

I want to share some of my experiences and notes on managing “choice overload”, becoming an efficient learner, and mastering a field. In particular, this mini-series will answer three questions I hear a lot from people starting out in our industry: “Where do I start?” (Part 1 – The Paradox of Choice), “How can I become good at this topic quickly?” (Part 2 – The Power of Deliberate Practice) and “How can I finally master this field?” (part 3 – Mastery).

Whether new or established, everyone in the InfoSec industry is trying to bring their skills to the next level, learn new skills, or strengthen our existing set of skills. The industry has an enormous range of fields and subfields to choose from. Choosing which to learn next is a very personal decision. Your choice will be based on your own personal circumstances, abilities, preferences, and life goals. For example, someone who enjoys talking to people and managing projects will likely enjoy different sub-fields of InfoSec compared to someone who does not. There is no one “right” path through InfoSec.

In the back of our minds we can all sense an overall lack of direction. We’re constantly pulled one way or another by the opinions of others and by our changing moods. In order to achieve a sense of direction, it is important to ask ourselves hard questions and make some difficult choices. Asking ourselves these hard questions is necessary in order to avoid drifting aimlessly. It is easy to hope the world will write our life story for us, letting mechanisms like reward and punishment, fear, and the easiness of an option tell us what to do. But people who follow this path usually end up unsatisfied and feeling like they’ve reached a dead end. Hard choices give us the power to dictate our own path and help us make the choices that suit us best. Don’t shy away from hard choices.

“He who has a ‘why’ to live can bear almost any ‘how’.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

InfoSec is very unlike many traditional career paths, which are often heavily structured and easy to drift through. In InfoSec, by contrast, we are often overloaded with possibilities and opportunities by the digital world.

This world of opportunities can be exciting and liberating but it can also be intimidating. It can be hard to know how to navigate all the possibilities. If we aimlessly try too many different things we might never develop solid skills in any area. On the other hand, if we just settle and focus on a single job that is unsuited to our nature we may end up bored and unfulfilled and end up trying to find fulfillment through other activities or addictions.

This lack of purpose can cause us to feel insecure or envious of others who have solid accomplishments, can make us fragile to criticism, and can make us more likely to be mean-spirited; putting down others in order to cover up our own insecurities.

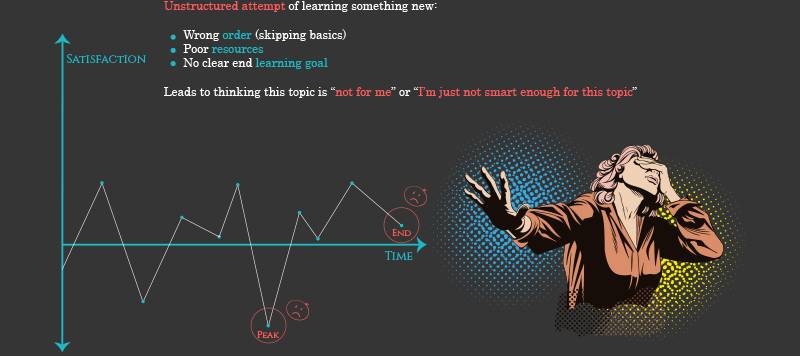

A better path is to find a direction that aligns with our life goals, interests, and natural tendencies by trying new fields and moving on if they do not suit us. Some of the things we try may end up being a negative experience for us. These negative experiences can be demoralizing or make us feel like we aren’t smart enough for that area. But these situations aren’t always an accurate reflection of what we are capable of and so it is important to understand how they can affect us and why we might have negative experiences of a field that we might be well-suited to.

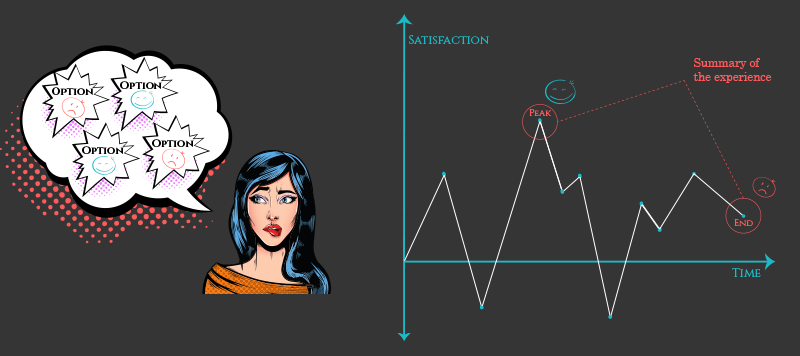

In their paper “Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes”, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Barbara Fredrickson discuss a phenomenon called “The Peak End Rule”. This is the mechanism our brain uses to summarize our experiences, and which influences whether we would like to have that experience again. Their paper argues that our memories about the pleasurableness of our past experiences is not determined by the overall proportion of pleasure versus displeasure in the experience, or even how long it lasted, but rather that it is almost entirely determined by a few “snapshots” of how we felt about the experience—most importantly how we felt at the (high or low) peak of the experience and how we felt when the experience ended.

Importantly, they observe that our memory of the experience is not based on how we actually felt about the experience on average.

Understanding Traumatic First-Time Learning Experiences

Suppose for example that you want to learn how to reverse-engineer compiled applications because you know that you like solving puzzles and are very detail-oriented. Perhaps you think RE is just the right thing for you. Suppose you are also impatient and fail to set appropriate learning goals and don’t choose good resources to help you learn. Worse still, suppose you prioritize your learning goals and choose to skip past the basics and dive straight into something exciting and advanced instead.

In this scenario, you will probably start off very excited and make some superficial progress by performing easy tricks to get started. But quickly you get stuck and don’t know how to proceed. Perhaps you haven’t set up a proper lab environment or get confused when you see assembly instructions for the first time. It is likely that you get frustrated and give up.

The “Peak End Rule” means that your brain will likely remember this experience as overall unpleasant because of its unpleasant “peak” of frustration and the disappointing end. This makes it more likely that you will think of reverse-engineering as “not for you”, or that you aren’t as smart as people established in the reverse-engineering field who don’t seem to struggle with it. The “Peak End Rule” means you are likely to choose not to repeat this experience. But had you structured your learning better you would perhaps have avoided the unpleasant experience and found that reverse-engineering is a good fit for you.

There are, of course, exceptions to any rule. Some people naturally thrive on frustration and don’t give up easily even after a bad learning experience. But the point is we should not mistake a bad learning experience for being “stupid” or “incapable”. Often it is just the result of an unstructured learning attempt and if we had instead tried with a better learning strategy we would have succeeded and found the whole experience much more pleasant and successful.

In short, knowing how your brain works and that memories are often not accurate assessments of your abilities can help you circumvent this error and try again, hopefully planning it better and ending up with a more pleasant and successful experience.

Setting proper learning goals and choosing the right learning resources can help avoid negative learning experiences. But how can we choose the right resources to use? Choosing the right resources isn’t some grand life decision, but rather it is just a decision to make a structured attempt at learning something new. But choosing well is critical to reaching our learning goals.

Suppose for example that you are new to the InfoSec field and have decided to choose “pentesting” specializing in web application security as your sub-field. What resources should you start with? Perhaps you will do a quick Google search and check the top links. Perhaps you will find meta-resources like the GitHub repository Awesome Hacking. Quickly you will find there is no shortage of resources to start with.

Counterintuitively, having so many options probably won’t help you choose. It is very easy to become overwhelmed with all the options, not knowing which will be the best use of your time. Having so much choice can also make it easy to give up without choosing at all. This is the phenomenon known as “choice paralysis”.

It is a common mistake to think that more information means we will make better decisions, but repeated studies have shown this is not the case. In his book “The Paradox of Choice”, Barry Schwarz shows that when presented with 10 or more options for making a choice, people consistently make worse decisions than those who are given fewer. The exact threshold varies between different studies, but all agree that when presented with too many options, people either make a “default” decision or end up getting frustrated and not choosing at all. Even when choosing a good option, they are often less satisfied with their choice compared to someone who was presented with fewer choices because they spend much more time second-guessing whether they made the right choice.

It is a common mistake to think that more information means we will make better decisions, but repeated studies have shown this is not the case. In his book “The Paradox of Choice”, Barry Schwarz shows that when presented with 10 or more options for making a choice, people consistently make worse decisions than those who are given fewer. The exact threshold varies between different studies, but all agree that when presented with too many options, people either make a “default” decision or end up getting frustrated and not choosing at all. Even when choosing a good option, they are often less satisfied with their choice compared to someone who was presented with fewer choices because they spend much more time second-guessing whether they made the right choice.

In his book, Schwarz shows that a person’s dissatisfaction level after their choice depends on how they approach the decision, and he divides people into two groups which he analyzes separately. He calls the group “maximizers” and the second group “satisficers”.

Maximizers versus Satisficers

The first of the two groups Schwarz calls “maximizers”. A maximizer does not merely want their needs to be satisfied, but rather wants to make the best possible choice to achieve the best possible outcome. Most of us approach making decisions with the maximizer mindset or did so in the past. By necessity, maximizers can’t be sure they have found the best option until they have looked at all the possible choices. This means it is easy for maximizers to become overloaded with options, feeling compelled to evaluate all possible choices before being able to choose.

If the number of choices becomes too big, the cognitive stress and time to check every possible option can quickly become impossible. This is where maximizers end up getting frustrated by the complexity of their dilemma and become unable to choose. This frustration is called “choice paralysis”. Even when they do eventually choose, the complexity of the choice often leads to regret and second-guessing of that choice. Counterintuitively, this emotional cost can also interfere with their ability to make a good decision. The irony is that maximizers can often overload themselves with so many options that they make bad decisions, regret their decisions even if they are correct, and also lose sight of the opportunity costs associated with making the maximized decision in the first place.

If the number of choices becomes too big, the cognitive stress and time to check every possible option can quickly become impossible. This is where maximizers end up getting frustrated by the complexity of their dilemma and become unable to choose. This frustration is called “choice paralysis”. Even when they do eventually choose, the complexity of the choice often leads to regret and second-guessing of that choice. Counterintuitively, this emotional cost can also interfere with their ability to make a good decision. The irony is that maximizers can often overload themselves with so many options that they make bad decisions, regret their decisions even if they are correct, and also lose sight of the opportunity costs associated with making the maximized decision in the first place.

The second group Schwarz describes is the “satisficer”. Unlike maximizers, satisficers settle for making a decision that is “good enough” without worrying about the possibility that there might be a better option out there. That does not mean that satisficers choose at random. Rather, satisficers use some criteria to discard options that are not good enough, but they affirmatively stop looking once they have found an option that meets those requirements. This “good enough” strategy makes overloading themselves with options far less likely.

By understanding whether we are making decisions as a “maximizer” or a “satisficer”, we can make better decisions. For example, by using the satisficer mindset we can have a clear learning goal and set our requirements to meet that goal and thus avoid becoming paralyzed by so much choice, or becoming frustrated from the cognitive overload of trying to assess all of the options.

When it comes to choosing the right resources for a skill we want to attain, the first step is to identify the sub-components of the skill we will need to learn, and set proper learning goals for ourselves. We can apply the “satisficer” mindset to learning resources by first excluding those which don’t meet our goal, and then choosing the first which is “good enough”.

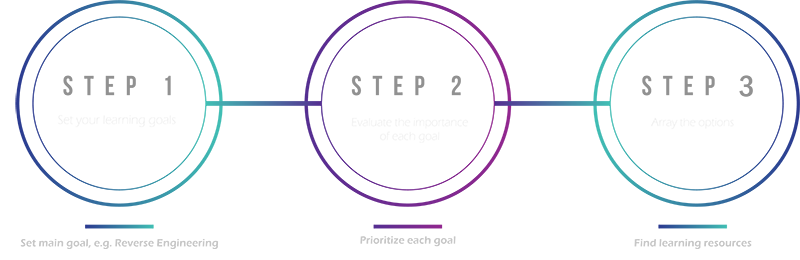

Here are a few steps you can take to get through the information overload and pick the resources that will help you achieve your goals.

Step 1: Set your learning goals. Don’t underestimate the importance of setting learning goals, sub-goals, and sub-sub-goals. Figuring out the overall goal is usually pretty simple but setting the learning sub-goals requires effort: we often don’t know enough about a field to accurately determine all the learning goals before we start. This means we will have to do a bit of research and figure out what skills will be required for us to reach our overall goal and as ask people who already possess these skills. If you can’t get the perfect big picture, that’s okay! Take what you have and split it into sub goals. You can add the missing sub goals later after you gained more insights and identified your knowledge gaps.

Step 2: Evaluate the importance of each goal. Some topics are more exciting than others. Some topics are more important than others. Take a critical look at the skills you are about to learn and prioritize them carefully. Keep in mind that learning the basics of your skill should be a priority in order to develop a solid basis in the field. If you skip ahead you will often miss important concepts that would’ve helped you understand the more advanced stuff in way more detail.

Step 3: Identify your options. After setting your learning goals you need to find the right resources. Your learning goal will help you set the minimum criteria of the resources you are about to pick. It is usually less stressful and more productive to approach this stage with the “satisficer” mindset and focus on finding resources that are “good enough”. Pick a few resources that meet your requirements.

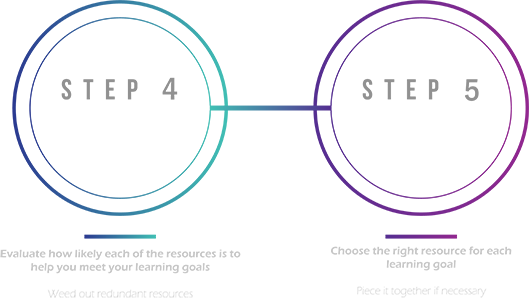

Step 4: Evaluate how likely each of the resources is to help you meet your goals. After picking several good resources, weed out any redundancy in them. If two resources have overlapping subjects then determine which one is more likely to help you achieve your learning goal.

Step 5: Pick the winning resources. It doesn’t matter if no single resource covers everything you need to achieve your entire sub-goal. By breaking down the sub-goal further, you can cover it with multiple different resources.

In the next parts of this series, I will cover questions like “How do I manage all the distractions when trying to learn?”, “How do I become a more productive learner?”, and “How do I master a field?”.